Image Generated with AI ∙ January 23, 2024 at 11:20 AM *

Who built the first computers?

Published 1/24/2024

Computing History Series, Part 1

Read time:

Introduction

When we think of a computer most of us today would conjure up a mental image of a Desktop or Laptop PC, and if you are of the younger generation, you might perhaps think of a smartphone or some tablet device. Rarely do we stop to think about what computers really are, much less where they came from, and who built the first computers. Yet, it is important to consider these things because they enhance our appreciation for the devices that we use on a daily basis.

For this reason, I will be publishing a series of articles on Computing History beginning with an understanding of what computers really are, a brief history of computing, a look at the first computers ever built, and then finish it off with some thoughts on what I believe will be the future of the computing industry.

What is a computer?

Over the years there have been many attempts at defining what a computer really is. According to Wikipedia, a computer is "a machine that can be programmed to carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically." 1

Another definition offered up by Merriam-Webster Online defines a computer as "a programmable usually electronic device that can store, retrieve, and process data". 2

These descriptions of programmable electronic devices that are capable of carrying out mathematical operations as well as store, retrieve, and process data certainly describe what we have come to know as computers in our modern age. However, in reality the English word "computer" was derived from the Latin word "com-putare" which means "to count, sum up, reckon together". 3

In this context, the Latin root word for "computare" might prompt us to think of ancient times when people would gather by the fire and use pebbles and counting sticks to perform basic arithmetic operations such as adding and subtracting. This may seem crude by modern standards, but we know that people once used this as an early rudimentary accounting system during the rise of humanity's earliest civilizations. These early accounting systems were invented to ease the burden of counting, adding, and subtracting on a large scale.

This may have been exactly what the root origin of the word "computare" was meant to convey. The act of computing in Latin suggests gathering with others to "reckon" something, which is an English word meaning to "establish by counting or calculation; calculate".

So we see that the root Latin word for a computer refers to a device that can be used to perform calculations. This intuitively makes sense, given that a computer is a machine that performs calculations. By this definition, any device that can be used to calculate something is performing the act of computing, even sticks and stones.

By extension, a device that performs computation on our behalf helps ease the burden of calculating, such that we do not have to rely on human memory alone. It's a way of automating what could in some cases be an extremely heavy burden, such as the burden of calculating and keeping track of humanity's needs on a very large scale. Now we can see how this early "computing" system would have been extremely useful during the rise of the first human civilizations, a task that may not otherwise have been possible without some form of counting system.

These ideas help us understand what a computer really is. The truth is that computers are an extension of the human mind. If we think about it, the human mind itself is a calculating device, our senses are optimized for information gathering. It is within this framework of data collection, memory management, and information processing that occurs within the human mind where true computing takes place.

We will now take a brief look at some of those early systems that were created to ease the burden of computing on a massive scale.

Human Writing and Early Mathematics

When we look at the dawn of human history, we find traces of our earliest ancestors who established the first building blocks of civilization. While the exact moment when this occurred is a topic that historians and archaeologists still debate, we know of two examples in human history that marked humanity's first attempts at performing calculations at a large scale: Egypt and Mesopotamia.

In particular, the geographical region known as Mesopotamia, or as archaeologists like to call it, "the land between the rivers", was home to some of humanity's earliest cities ever built, such so that the region is often referred to as "the cradle of civilization". There, during this "birth" of human civilization, we not only find the earliest examples of ancient, pyramid-like structures called "ziggurats", but also one of the most ancient forms of human writing, known as "cuneiform".

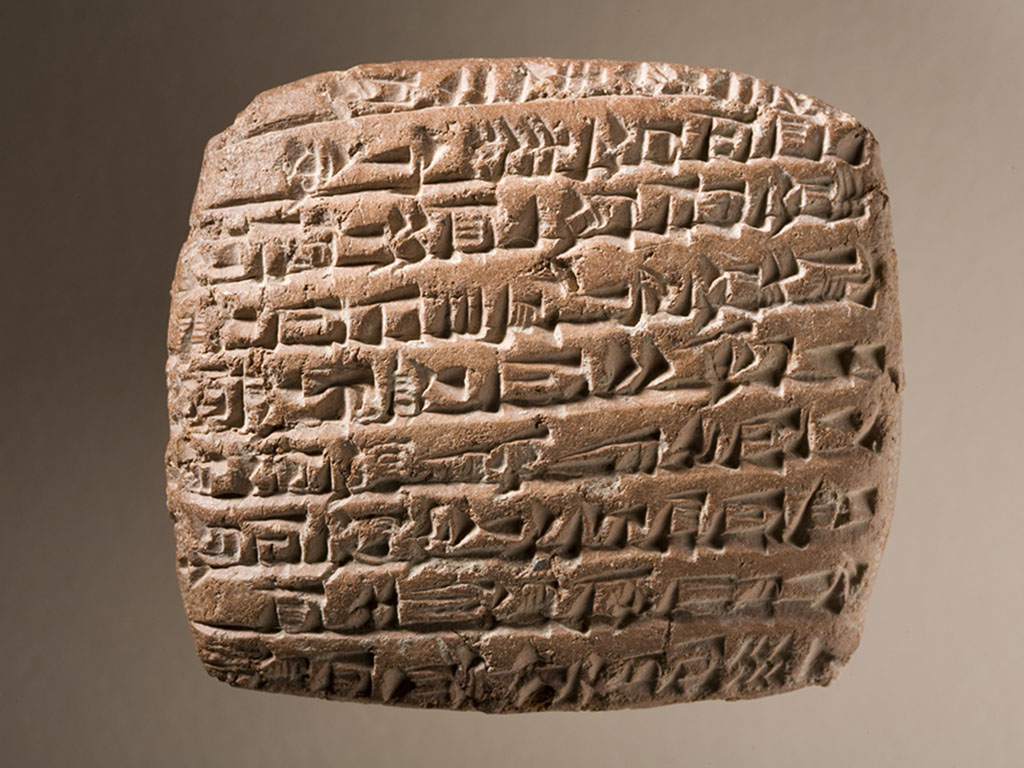

Cuneiform was first put into use as early as 3200 BCE by a group of people known as the Sumerians, a term derived from the word "Sumer", which was a region of southern Mesopotamia located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

These ancient Sumerians first put cuneiform into use through the clever process of imprinting marks onto soft clay tablets, which would then harden as the clay material dried out. These cuneiform clay tablets represent some of humanity's earliest attempts at recording information.

Likewise, ancient Egyptians may be just as old as the Sumerians. Ancient Egyptians used a writing system known as Egyptian hieroglyphs. This writing system is completely distinct from cuneiform. Hieroglyphs were much more complex due to their depictions of various objects, including animals and people. Furthermore, ancient Egyptians were not content with just using clay tablets, they wrote by directly chiseling hieroglyphs onto stone walls.

Whereas cuneiform was quick and easy to produce, hieroglyphs used images to depict ideas, and required great skill to produce. Some of these ancient writings date as far back as 3200 BCE (over 5,200 years ago) which would put them at right around the same time as the Sumerians were producing cuneiform.

.jpg)

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, circa 3200 BCE

Image Credit: © William Matthew Flinders Petrie **

(3 June 1853 – 28 July 1942) - Egyptian Civilization Published in 1930

Of course, ancient Egypt is also known for producing the great pyramids that have survived for thousands of years as landmarks of Egyptian engineering greatness, megalithic monuments whose precise craftmanship continue to astonish historians and archaeologists even to our present day, the most famous of which being the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The first computing devices were those tools that ancient humans invented to aid in their laborious work of calculating and measuring distance, height, width, weight, angles, and all manner of mathematical calculations that were needed in order to achieve their task of building those megalithic monuments that continue to amaze us today.

The events that occurred in those days are of supreme importance with regards to computing history because they document the point at which humanity began to rise up "out of the mud" as historians like to put it. It was no coincidence that the rise of these first human civilizations correlates with the invention of writing and early mathematics, a monumental phase in human ingenuity that cannot be overstated. Without this critical junction, humanity may very well still be counting with sticks and stones.

Ancient Computational Devices

It is at this point where we begin our analysis of computing history, at the very dawn of human civilization. Over a great span of time, thousands of years, humanity grew from those initial first steps to becoming the most dominant form of life that exists on Earth. Yet, those initial discoveries give us a glimpse into the early beginnings of what we now refer to as "computers".

As we think back on those early civilizations, with their cuneiform writings and ancient hieroglyphs, we start to understand the computations that were necessary for humanity to move ahead, and the tools that were invented to ease the burden of those calculations. It may seem trivial, but in the span of humanity's existence, it was perhaps the most significant event in human history.

In the case of those Egyptian pyramids, there are often great debates between scholars over how, exactly, these were built. The most basic theory is that the huge stones were carved out using copper chisels, and that they were then dragged and lifted onto their final resting place. As to how the stones were lifted, one theory suggests that ramps may have been used, or perhaps a system of levers and/or pulleys. Or, as materials scientist Joseph Davidovits has put forth, the huge blocks may have been "cast" into place, similar to how modern construction methods use molds to build concrete slabs.

According to some estimates, the Great Pyramid of Giza consists of approximately 2.3 million blocks of limestone and granite, along with some 500,000 tonnes of mortar that was used during its construction.

The bottom line is that while there really is no definitive historical evidence to support any of these theories, we do know that some method had to have been used. This all but guarantees that at least some of the tools that were invented must have been used as computational devices to ease the burden of calculating at such a large scale. These "ancient computational devices" were the first precursors to modern-day computers. It is difficult for me to envision a scenario where such megalithic monuments could have been constructed without some form of computational device, if only to count the sheer number of resources that were needed.

Computation as an abstract concept

The ideas that sprang forth back then out of necessity are still the same techniques we use today to carry out mathematical and logical computations, to record, process, and retrieve information. Back then, humans used ancient writing techniques to transfer their thoughts onto some form of medium (for example, clay tablets or stone walls). The medium upon which their thoughts were transcribed determined how long those thoughts were preserved (in some cases even thousands of years). The process was so ingenius that we are capable of reading those thoughts thousands of years into the future. In reality, their goal of preserving these thoughts was a complete success despite having rudimentary tools to accomplish this.

Note that the process I just described involves "reading" and "writing" information onto some permanent material for long-term archival. Nowadays, in computing terms, we would refer to this process as Input and Output, or I/O. It's the process of taking raw data and outputting it to a form that is readable by others.

In reality, the act of chiseling words onto stone walls is no different than a computer writing data to a storage array on a server. In this sense, the act of information processing today is remarkably similar to how it was thousands of years ago. The difference is that this process, which once required a tremendous amount of effort, has now been made relatively easy through the use of modern computers.

As a result, those early counting systems have paved the way for algebra, geometry, and calculus. Likewise, those early measuring tools have been developed to such extent that humans are now capable of measuring distances at the atomic scale. We now have particle colliders that can smash atoms, and space telescopes that can peer into the farthest reaches of the known Universe.

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN, a testament to

modern engineering and mathematics

Humanity's progress has been truly astonishing, in part thanks to the computing devices that have emerged over the last five thousand years since humanity first learned to write on stone walls and clay tablets.

In addition, the sharing of information between humans has now become more accessible than ever thanks to the invention of the Internet, which is the technology that makes this all possible. Likewise, on this day, the 24th of January of the year 2024, I, a human, had thoughts that I transcribed into digital form. I uploaded those thoughts onto this web server where you, the reader, now have access to them. Now, you may be reading these words merely days after this article was published, or you may be reading this years, or even decades, into the future.

Ironically, the act of writing on a computer and sharing ideas for the whole world to read may seem trivial to some technologically advanced civilization far off into the future, and so it would seem that we are the Sumerians compared to them. Our fastest and most powerful computers are like copper chisels to a civilization just one percent more advanced than us, and our most complex mathematical and physics equations are like pebbles and counting sticks to the future generations of humanity that will one day master the concepts of computation.

No matter where technology takes us into the future, we owe it to ourselves to take a look now and then at computing's earliest endeavors. There is so much we can learn from what these early humans were able to achieve with such few resources.

In our next article in this series, we will take a look at the first uses of computing technologies which allowed humanity to build even greater civilizations.

- "Computer" Wikipedia Entry

- Merriam-Webster Online

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- Google Search, Definitions provided by Oxford Languages

- "Egyptian pyramid construction techniques" Wikipedia Entry

- "Great Pyramid of Giza" Wikipedia Entry